|

May 6th 1970

|

|

|

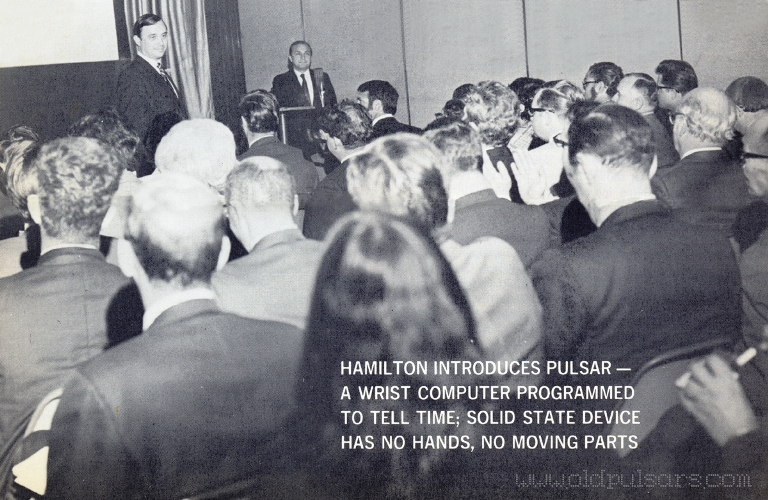

On May 6th, 1970, the announcement of the world's first digital watch was made at a press conference held at the Four Seasons Hotel in New York. Pictured above is George H. Thiess of Electro/Data (standing) being introduced by Hamilton's CEO, Richard J. Blakinger (at the podium). Thiess went on to discuss the watch and how it works and how it would change the way the world would tell time. You can read what happened from here on by going to the History section.

|

|

|

Prior to the press release, five different statements were prepared for the event by Jack Bernstein Associates of New York. The statement below has never been published but maybe now, forty years later, this one may have been a better choice than the two we have seen so many times. This statement seems to really put the Pulsar in perspective, now that we have seen the impact the Pulsar has made in the field of horology.

|

|

FROM SUNDIAL TO WRIST COMPUTER The Evolution of Timekeeping

|

|

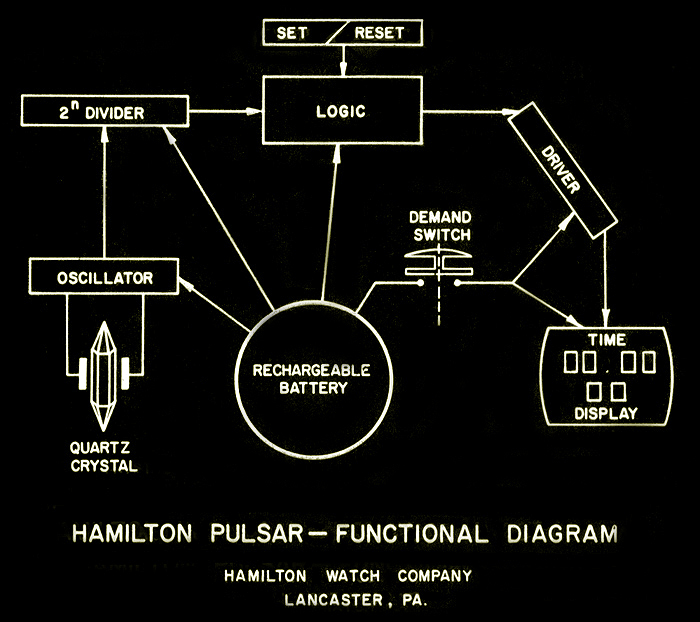

It began in 1957, when Hamilton Watch Company introduced the world's first battery-operated wristwatch. This revolutionary watchmaking concept incorporated the first basic change in portable timekeeping in almost 500 years by substituting a tiny energizer for the mainspring. During the 1960s, the process was continued through the production of tuning fork watches and, very recently, quartz crystal timepieces have been developed which offer improved accuracy. But they still required mechanical action to drive the watch hands. Then on May 6, 1970, Hamilton introduced PULSAR - - the first wrist computer for telling time. Through the application of solid state electronics and computer logic circuitry, PULSAR eliminates the need for watch hands or any moving parts and provides unexcelled accuracy, durability and dependability. This giant leap forward in measuring time caps more than 4,000 years in evolution of timekeeping. History's first time telling instrument was a sundial. Using it as his basic time measuring device, early man established the burning rate of ropes and crude candles and then knotted or marked them. Then as they burned, they showed the passage of hours in the night. As civilization advanced, so did the methods of telling time. The first recorded instance of time-telling by measured flow occurred in China over 4,000 years ago. The yellow Emperor, Hwangti, invented a water clock that was a rare combination of ingenuity, simplicity and efficiency. It consisted merely of a pierced brass bowl floating in a basin of water. Hours were calculated by the amount of time it took the bowl to submerge. Later the Greeks developed and refined the Clepsydra, a water clock, which kept track of time with only periodic attention. In other parts of the world, forerunners of the hourglass, using sand instead of water, were being devised. Numerous ingenious modifications of the basic water-metering system were invented, many of them converting the flow of water into mechanical energy which was used to operate simple machinery. In some cases small water wheels, run by escaping water, turned axles which wound or unwound cord at a more or less even rate, indicating time elapsed. In other, a float was attached to a pulley which turned a hand on a dial as the water level lowered. However, all such devices were, by the nature of their motive power, self-limiting, since water is unstable medium. While they might be refined infinitely they could not be basically improved. One such advancement from the Clepsydra was responsible for the first know historical mention of the word "clock", when it was presented to the King of France by Pope Paul I in 760 A.D. During the Crusades, clumsy mechanical time contrivances, operated by weights, were brought to Europe from the East. These, however, were totally unreliable and were merely curiosities and playthings for the mobility. Then, starting in 1480, all previous time-keeping devices were challenged and superseded, by the invention of the Nuremberg locksmith, Peter Henlein, who constructed a portable, mechanical, spring-driven timepiece. This mechanism and its later counterparts were known, because of their shape, as "Nuremburg Eggs". They were made of iron, enormously heavy, with a single hand to tell the hour -- and they were not very accurate. Because of their great weight, the wealthy used "bearers" who consulted the dial and spoke the time when asked to do so. Nevertheless, they were the first all-weather, independent, portable time-measuring instruments to appear, and were the ancestors of all horological devices developed from the fifteenth century to now. It should be noted, too, that although the "Nuremburg Eggs" paved the way for vast improvements in clocks, they were, themselves, the first watches. The first important change in these primitive watches came in 1530, when brass was substituted for iron in their construction. It proved both lighter and more efficient. The first wristwatch appeared in 1571. "A wristlet in which was a cloche" (the Elizabethan spelling of clock) was constructed by Bartholomew Newsam, official clockmaker to the English court, and presented to Queen Elizabeth. The relatively rare watches of this period were not distinguished by great accuracy. They varied as much as one hour in twenty-four. What they lacked mechanically, however, was offset by their elaborate cases which were executed by the foremost jewelers and metalsmiths of the time. Mechanical improvements continued to be made and pocket-size watches, in oval shapes, were regularly produced, although in small numbers and only for the wealthy. In 1635, Paul Viet, a young French watchmaker, made the first watch with an enameled dial, and in 1670 two of London's leading watchmakers, Knibb and Quare, added the first minute hands to watches. The most important deficiency in both watches and clocks was that their coiled mainspring exerted diminished power as they ran down. But in 1685, Dr. Robert Hooke, of England, invented the balance wheel which remedied this and represented a gigantic stride forward in making watches more dependable and accurate. Early in the eighteenth century repeating watches -- now circular in shape in stead of oval -- were developed. These struck the hours and were therefore known as "blindman's watches". The combined impact of the minute hand and the increased accuracy supplied by the balance spring gave watches a new and practical importance. Doctors were among the first to see their value, and in a comparatively short time watches were in widespread demand. John Harrison, of London, constructed the first marine chronometer, to be used for navigation. At the end of a five-month voyage in 1762, this new timepiece, which was not a clock but a large watch, was in error just over a minute, a record that would be good even today (1970). America's watchmaking industry started in 1809 when Luther Goddard opened a factory in Shrewsbeury, Mass. Three years later, James and Harry Pitkin set up a small plant in Hartford where they made the "Pitkin Watch" -- the first machine-made timepiece in America. During the next century and a half, some of the best scientific and artistic brains in the country contributed to the development of the industry, culminating in the creation of the PULSAR.

|

| Copyright 2010, www.oldpulsars.com |